PUBLICATIES - NPK-BERICHTEN

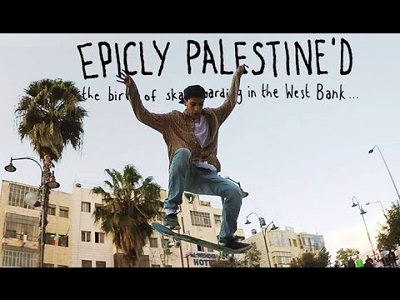

Skaten op de Westelijke Jordaanoever en verder leven in Gaza: twee korte films

Kickflicks over Palestine laat zien wat skaten voor de jongeren op de Bezette Westelijke Jordaanoever betekent.

De korte film What's going on? van Marcel Loermans en Ingrid Rollema laat zien hoe Gaza verder gaat.

Hossam al-Madhoun, theatermaker, geeft in een interview met Pam Bailey zijn visie op de situatie in Gaza:

Mental health in Gaza: a subterranean malaise

Hossam Al-Madhoun (Photo: Pam Bailey)

As the international director of We Are Not Numbers, I interact daily with many young adults in Gaza, ages 17-29. This is the age when they finish high school or university and emerge into a crippled economy where about 60 percent of them will be unable to find jobs. Too much idle time, unable to afford marriage, memories of too many wars and scholarships lost due to the blockade.

In just one recent week, I found myself grappling with:

o A distinguished colleague, an NGO head who normally is a rock upon which we all lean, dropped out for days. He was coming to grips with the sickening reality that he would never be allowed out of Gaza by the current “regimes” in Israel and Egypt. After numerous previous attempts, he tried to join the crowd heading to Mecca for the Hajj, and even then was turned back. Clearly, he has been “blacklisted.” His new WhatsApp profile icon: “I am here to stay.”

o A 20-year-old university student had been preparing to leave for months after earning a scholarship to a school in Spain. He was assigned to the last of the buses to cross from Gaza to Egypt through the Rafah gate—but it was turned back at the border. The crossing hasn’t opened since. (The crossing had been closed for the previous 52 days, and there are about 15,000 people still on the waiting list to exit Gaza via Rafah.) “It’s my destiny,” he told me on Facebook chat, when I tried to find him after not hearing from him in days. “It’s a life without hope, a life without a future. Happiness and hope never last. Maybe because you are not in Gaza you can say that’s not true, but living here eradicates all the good feelings.” His new Facebook profile photo: the mask of the Joker.

o Another youth carved deep cuts into his arm with broken glass. The cuts were not placed correctly to end his life; rather, they were a crude call for help, a shout of “I am here!” into what appeared to him to be a mute universe. His Facebook profile photo: His face only barely visible behind a curtain of shadow, as if he is slowly disappearing.

Alarmed at the collective depression I sensed among virtually everyone to whom I talked, I asked my project manager what we should do to help. “But everyone is depressed in Gaza; it’s all a matter of degree,” he responded.

According to Hossam Al-Madhoun, a therapist at the Maan Development Center in Gaza, suicide is on the rise in the Strip, despite the fact that it is haram (forbidden) in Islam. “There is at least one every day, although most are not being publicly reported by the Hamas government,” he says. “This is a dramatic change from 20 years ago, when there might be one every few years. Especially since the summer attack by Israel last year, there has been a huge increase.”

The most at-risk are youth and young adults, who have the highest hopes but also the highest unemployment—and are just discovering their dreams too often turn to dust. Yet most of the formal psychosocial support programs in Gaza that receive international funding are for children. In part as a result, Al-Madhoun says, the quality of mental-health care in Gaza is highly variable, and the most-reputed centers such as the Gaza Community Health Program are overloaded.

The other challenge is that anything labeled “therapy” or “psychological” (heaven forbid you say “psychiatric”) carries a heavy social stigma. In the minds of most Gazans, admitting to emotional problems is tantamount to exposing yourself as “weak” (a very negative quality). And if someone develops a serious mental illness, such as the psychosis one young friend recently developed, the common assumption is that he or she is possessed, and a sheikh is called in. Even meditation is a bit suspect; I have connected several young people to a friend who teaches the relaxation technique via Skype, but must be careful not to mention it to anyone else. Trust, I have learned, is also in very short supply there these days; as a foreigner, safely removed from Gaza, I am a “safe harbor.”

“A disaster brings people together, but when repeated over and over, it’s not. Everybody is exhausted, too busy coping with their own troubles,” Al-Madhoun explains, adding that he also thinks the Arab culture tends to be more judgmental.

Drama as therapy?

Al-Madhoun uses drama to help Palestinians of all ages expose and manage their inner demons. Drama, as well as other forms of art, he says, is a way of “tricking” them into opening up, and in turn, accept help. He begins with relaxation and simple, fun role-playing; he then slowly eases them into improvisation.

“Drama is like magic,” he smiles. “It’s play, but serious play. Everyone ends up enjoying it, and then you reach a moment when you throw everything out there.”

Al-Madhoun first discovered his interest in drama in 1992, when he was 22 and was caught writing anti-occupation slogans on the massive cement wall that separates Gaza from Israel. He was detained and accused of being a member of the Palestine Liberation Organization, which Israel considered illegal at the time. He was jailed in Israel’s Ansar Prison in the Naqab (Negev) Desert for nine months. (The following year, the PLO was recognized by the UN as the official representative of the Palestinians).

Al-Madhoun says his months in prison changed him in two ways: “First, I learned how counterproductive politics can be,” he recalls. “In the prison, Hamas and Fatah fought each other constantly. I decided never to belong to a political party. “The second consequence was more positive. “I met theater in prison. The other prisoners put on a play, and I participated. I discovered that it is another form of resistance that can also educate and raise awareness of my people’s daily life under occupation: the wall, the checkpoints, the blockade, the humiliation at the crossing points. I decided I would study theater.”

And he did. When Al-Madhoun was released, he joined an amateur theater group in Gaza called Theatre for Everybody. The troupe was founded in 1987 during the First Intifada, performing both internationally and at home.

Unfortunately, however, “Theatre in Gaza is not as it used to be anymore,” says Al-Madhoun,”both because of the conservative government and the effect of the blockade on our economy. Culture can no longer be such a priority. Historically, theater could never be a primary income source in Gaza. But now, we can’t make anything from it. I used to participate in two to three productions per year, performing hundreds of shows in Gaza and in Europe. But since 2006, I have participated in only three productions and have not been able to perform out of Gaza due to the blockade.”

Drama, and all forms of art, does live on in Gaza, however, as a form of therapy. Al-Madhoun insists he is an actor and director, not a writer, but his poem, “Here we are, after the war,” captures so eloquently the angst of the people:

Wars are a very strange thing, difficult to describe, my friend.

War ends and you believe you survived.

But after a while, you realize that the war is still going on within you,

Chasing you in your dreams, in the destruction around you,

In the funerals and the sad faces in the streets and the markets,

In the sorrow of those who lost their beloved relatives.

Wars do not end or leave simply.

Suddenly your 11-year-old child wets his bed,

and your wife has nightmares;

You too, but you don’t admit it!

Your clever daughter is getting very low marks at school

and she doesn’t know why.

Suddenly your kind and nice neighbor doesn’t stop yelling

and shouting at his wife and kids.

Day and night and no one can stop him.

Your eldest son wakes up in panic with any strange sound.

A knock at the door, a cup falls and breaks,

a fast car’s wheels scream in the street.

After war, nothing remains the same.Before war, there were no people living in

half-destroyed homes or sheltering in schools.

Before war there were no children or women

looking for something to eat in the garbage.

Before war there weren’t thousands of beggars of all ages:

Children, youth, women, men.

Before war there weren’t 50.000 people without homes.

Before war there weren’t 800,000 children suffering

from fear, nightmares, bed-wetting, sleep disturbance, anxiety.

Before war… before war … before war… And after the war?

Pam Bailey - Mondoweiss, 25 september 2015

Pam Bailey is a freelance writer based in Washington, DC, who also works as special assistant to the chairman of Euro-Mid Observer for Human Rights and international director of We Are Not Numbers.

Actuele NPK-berichten

Er zijn inmiddels meer aanbieders van Palestijnse producten.

Er zijn inmiddels meer aanbieders van Palestijnse producten.